Quantum relative entropy

In quantum information theory, quantum relative entropy is a measure of distinguishability between two quantum states. It is the quantum mechanical analog of relative entropy.

Contents |

Motivation

For simplicity, it will be assumed that all objects in the article are finite dimensional.

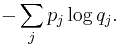

We first discuss the classical case. Suppose the probabilities of a finite sequence of events is given by the probability distribution P = {p1...pn}, but somehow we mistakenly assumed it to be Q = {q1...qn}. For instance, we can mistake an unfair coin for a fair one. According to this erroneous assumption, our uncertainty about the j-th event, or equivalently, the amount of information provided after observing the j-th event, is

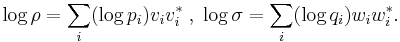

The (assumed) average uncertainty of all possible events is then

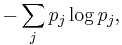

On the other hand, the Shannon entropy of the probability distribution p, defined by

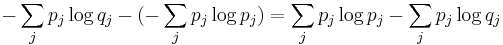

is the real amount of uncertainty before observation. Therefore the difference between these two quantities

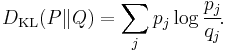

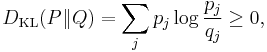

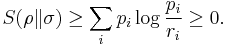

is a measure of the distinguishability of the two probability distributions p and q. This is precisely the classical relative entropy, or Kullback–Leibler divergence:

Note

- In the definitions above, the convention that 0·log 0 = 0 is assumed, since limx → 0 x log x = 0. Intuitively, one would expect that an event of zero probability to contribute nothing towards entropy.

- The relative entropy is not a metric. For example, it is not symmetric. The uncertainty discrepancy in mistaking a fair coin to be unfair is not the same as the opposite situation.

Definition

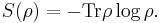

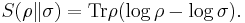

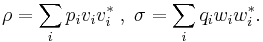

As with many other objects in quantum information theory, quantum relative entropy is defined by extending the classical definition from probability distributions to density matrices. Let ρ be a density matrix. The von Neumann entropy of ρ, which is the quantum mechanical analaog of the Shannon entropy, is given by

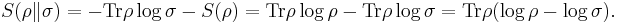

For two density matrices ρ and σ, the quantum relative entropy of ρ with respect to σ is defined by

We see that, when the states are classical, i.e. ρσ = σρ, the definition coincides with the classical case.

Non-finite relative entropy

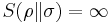

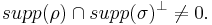

In general, the support of a matrix M, denoted by supp(M), is the orthogonal complement of its kernel. When consider the quantum relative entropy, we assume the convention that - s· log 0 = ∞ for any s > 0. This leads to the definition that

when

This makes physical sense. Informally, the quantum relative entropy is a measure of our ability to distinguish two quantum states. But orthogonal quantum states can always be distinguished, via projective measurement. In the present context, this is reflected by non-finite quantum relative entropy.

In the interpretation given in the previous section, if we erroneously assume the state ρ has support in supp(ρ)⊥, this is an error impossible to recover from.

Klein's inequality

Corresponding classical statement

For the classical Kullback–Leibler divergence, it can be shown that

and equality holds if and only if P = Q. Colloquially, this means that the uncertainty calculated using erroneous assumptions is always greater than the real amount of uncertainty.

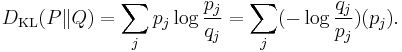

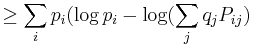

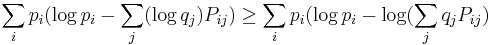

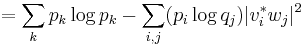

To show the inequality, we rewrite

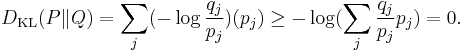

Notice that log is a concave function. Therefore -log is convex. Applying Jensen's inequality to -log gives

Jensen's inequality also states that equality holds if and only if, for all i, qi = (∑qj) pi, i.e. p = q.

The result

Klein's inequality states that the quantum relative entropy

is non-negative in general. It is zero if and only ρ = σ.

Proof

Let ρ and σ have spectral decompositions

So

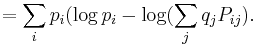

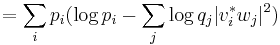

Direct calculation gives

where Pi j = |vi*wj|2.

where Pi j = |vi*wj|2.

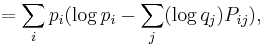

Since the matrix (Pi j)i j is a doubly stochastic matrix and -log is a convex function, the above expression is

Define ri = ∑jqj Pi j. Then {ri} is a probability distribution. From the non-negativity of classical relative entropy, we have

The second part of the claim follows from the fact that, since -log is strictly convex, equality is achieved in

if and only if (Pi j) is a permutation matrix, which implies ρ = σ, after a suitable labeling of the eigenvectors {vi} and {wi}.

An entanglement measure

Let a composite quantum system have state space

and ρ be a density matrix acting on H.

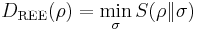

The relative entropy of entanglement of ρ is defined by

where the minimum is taken over the family of separable states. A physical interpretation of the quantity is the optimal distinguishability of the state ρ from separable states.

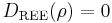

Clearly, when ρ is not entangled

by Klein's inequality.

Relation to other quantum information quantities

One reason the quantum relative entropy is useful is that several other important quantum information quantities are special cases of it. Often, theorems are stated in terms of the quantum relative entropy, which lead to immediate corollaries concerning the other quantities. Below, we list some of these relations.

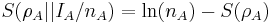

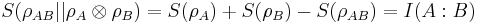

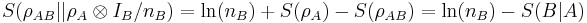

Let ρAB be the joint state of a bipartite system with subsystem A of dimension nA and B of dimension nB. Let ρA, ρB be the respective reduced states, and IA, IB the respective identities. The maximally mixed states are IA/nA and IB/nB. Then it is possible to show with direct computation that

,

,

,

,

,

,

where I(A:B) is the quantum mutual information and S(B|A) is the quantum conditional entropy.

References

Vedral V., 2002, Rep. Math. Phys. 74, 197, eprint quant-ph/0102094 * [1]